|

Contents –– name –– About the Transcription –– Bibliographic Information |

The Plough Boy JournalsThe Journals and Associated Documents The Plough Boy AnthologyDictionaries & Glossaries |

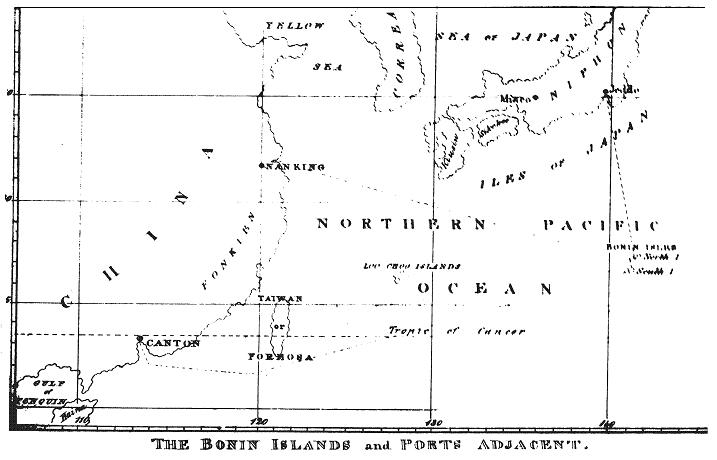

THE BONIN ISLANDS AND PORTS ADJACENT. |

A LETTERADDRESSEDTO THE BRITISH PUBLIC,ON THE OCCUPATION OFTHE BONIN ISLANDS.My dear Countrymen, The observations I have to make upon the advantages of the occupation of the Bonin Islands will not be characterized either by depth of thought or extent of information; a few plain sentiments, delivered in plain language, will fill the compass of these brief pages. I have often remarked that the successful issue of an enterprize was not due to the recondite nature of its principles or the multiplicity of contrivance, but to the adoption of, and the adherence to rules that were obvious in theory and easy in practice. And in the same way I have seen that conviction is not produced by far-fetched arguments and laboured declamation, but by simple statements and familiar proofs. To establish a communication with Eastern China, Japan, Loo-choo, and other islands and shores of this sea, on terms of equality and mutual respect, is an event which, at the first glance, |

appears so full of interest and utility, that no display of eloquence or depth of argument is necessary to enforce it. To find ourselves shut out and hindered from extending to multitudes of the human race the benefits of the gospel and the improvement of science, or even from gratifying a reasonable curiosity, is humiliating, especially when we learn, by experience, that neither knowledge, kindness, or any other recommendation can procure for us a momentary stay in Canton, except at the pleasure of delegated authority, but are liable to be thrust away forthwith, as if we had the plague or the leprosy, without protection from the laws of hospitality, or time to explain the reason of our coming. It will be said that some have visited the coast and met with friendly treatment, and that we are allowed to live at Macao with our families if we please; but here at Macao, on a jutting point of land like prisoners, we are hemmed in, partly with the sea and partly with a barrier, that is guarded, not by soldiers, nor by any thing in uniform, nor even in decent apparel, but, as if on purpose to insult us, by some of the most degraded beings in the empire. The mandarins teach the common people to despise us by every means in their power; these are not slow to profit by their instructions, and at certain periods, by threats, frighten all the timorous natives from our service, alleging that an in- |

tercourse with us infects the purity of the Chinese morals. A few days ago it was declared to be presumption in foreigners to ride in chairs borne by Chinese, without any exception in favour of invalids or delicate females, and it was thought better for men employed in this way to starve than submit to such a degrading employment. As to the visits which have been made to different parts of the coast, their desultory and flying character shews how much reliance could be placed upon the transient smile of a friendly reception. Nay, in some instances, highly emblazoned with attractive description, if the truth were told, it would appear that even this transient smile owed more to the lure of opium than to the feelings of humanity. However that may be, we know that a frown from a man in authority soon dissipates the semblance of a cordial welcome, and the stranger finds himself alone, while his benefactors are hurried away to do some act of penance for shewing him any favour. It is sometimes contended that the Chinese have a right to lay what restriction they think proper upon their trade with foreigners, and to drive them from their shores as often as they choose, who, if they do not like these terms, may go elsewhere in quest of better. But the question that demands an answer does not seem to be, what right they have to perplex commercial dealings, which they themselves have encouraged, or to treat us on all public |

occasions as destitute unprincipled men; – but, whether it be not advisable to take such steps as may, sooner or later, convince them that their opinion of us is erroneous, however flattering it may be to their pride and vanity to cherish it? The justice of declaring war against them would be questioned by many, and an embassy, unless it were conducted with a degree of firmness and resolution far different from any of its predecessors, would prove, like them, a melancholy failure. A Chinese has only two leading passions, fear and avarice; all the other feelings incidental to our nature are merged in these two dominant motives to action. If Christianity forbids us to use threatening, there is no rule of morals or religion that I am acquainted with, that hinders us from attempting to pursue a lawful object of commercial dealing upon equitable terms, wherever an independent spot is opened. This may work upon his principles of self-interest, while his apprehensions would be excited, without drawing a sword or bending a bow. This, I think, would be done with increasing effect and prosperity by a settlement at the Bonin Islands, which, while it would draw adventurers allured by the hopes of a gainful trade from the neighbouring shores, would give the English nation such a respectability in the eyes of all around, that contumelious usage and scornful language would soon cease to be applied to us. |

The Bonin Islands are about eight days' sail from China, five from Loo-choo, and three from Japan; and belong to the English, not only in virtue of a formal possession, but from the circumstance, that Englishmen have resided upon one of them for more than ten years; which gives us a title to them, arising from prior occupation, a title that is esteemed a good one by the law of nations. When I visited one of them, in the expedition of Captain Beechey, I found a hilly spot covered from the shore to the ridge of the mountain with vegetation, which abounded in curious and beautiful plants and trees. I never spent four days that afforded more interest or more instruction. I do not wish it to be understood, that I think them fitted to answer all the hopes of a husbandman who had come from the other side of the globe to better his condition; for the settlement I propose is not to be an agricultural, but a commercial colony; one that would be worth the nursing, not so much for its intrinsic value, as for the place and a name that we should thus obtain in the midst of these interesting countries. It is enough, that there is room sufficient for laying out gardens to raise vegetables for the table, and some variety of hill and dale for such walks and pleasure grounds as health and recreation might require. Those who have lived there in lonely seclusion, found the necessaries of life of such easy acquisition, that, when induced |

to leave from present circumstances, have afterwards expressed many longings to get back again to their sequestered but easy home. Here, under the management of a spirited and enlightened governor, Englishmen, Americans, and the natives of European nations, might enjoy all the security, and many of the comforts of home, in the very centre of those nations who have hitherto shut their doors against them. Some of the principal advantages may be summed up, a little more in detail, under the following heads, which will form the substance of this representation. First. The first class of advantages would result from the vicinity of the Bonin Islands to Loo-Choo, Japan, China and Formosa, by which a point of easy access would be afforded to native vessels from all those countries, a circumstance that would tend to promote an unfettered communication among them with foreigners, and of consequence, with each other. This would certainly be the case in a little time, whatever embarrassments they might at first be subjected to, from the authorities of their respective countries, where, with few exceptions, every effort to introduce foreign articles is checked and hampered by the ascendancy of local statutes. There would be found among them men of enterprize; such, for example, as the natives of the Fuh-keen province, who, urged forward |

by the hope of advantage, would disdain unreasonable and petty restrictions, and repair to a market near at hand, where the greatest choice of foreign articles might be had at the lowest prices. And it is not hard to conceive, that those who come to trade, would in time bring goods instead of money, which would assist the manufacturers at home, and consequently spread the benefits of such traffic to many hundreds besides themselves; which might induce the magistrates to allow the utmost extent of liberty in their power, or, what is far better, lead the legislature to repeal irksome and abortive laws. For governors, in this part of the world, though they often treat individuals with little ceremony or compassion, are rather fearful of exasperating a whole community, especially when they find them disposed to set up the rights of the subject against the encroachments of a magistrate. It will be said, perhaps, that experiment does not warrant us in expecting much advantage from this trade; for nothing finds a ready market save opium. But perhaps it would not require much ingenuity to prove, that the sale of opium stands in the way of lawful kinds of traffic, while it abstracts those monies which might otherwise have been applied to useful purposes in general commerce. Nay, I apprehend that it would not require much aid from the imagination to think, that as opium, when taken as a luxury, destroys every sinew of the body, and ener- |

vates the mind, and renders the person using it a fit companion only for the lost of the human race; so, as merchandize, it blasts and withers every kind of dealing that is mixed up with it. I hope it may not have this effect upon the religious books that have sometimes been circulated under its auspices. But we had forgotten our settlement, the fame of which, when once diffused abroad, would allure not only those who looked for gain, but entice others, from motives of curiosity, to come and visit it, who would not fail, on their return, to report among their countrymen what they had seen, and what kind of treatment they had experienced among the sons of freedom, religion and science. At this place of rendezvous, Chinese, Japanese, Formosans and Lew-chewans would meet and exchange their sentiments, if not by speech at least by writing, which would tend to establish them upon a footing of better understanding with each other, and diffuse a knowledge of the colloquial dialects, peculiar to each nation, among all the rest; while the prospect of advantage, and the comforts of home, would persuade Europeans to come hither to learn the Asiatic languages, that they might act as interpreters, which would enable us to dispense with that mutilated jargon in which all our mercantile transactions are now conducted. Secondly. One of these islands would be an eligible spot for establishments of a religious and |

scientific nature, where strangers might obtain every kind of instruction, and from whence books might be issued for the improvement of surrounding nations. As facilities for learning the eastern languages would be greatly multiplied by this means, so conveniences for printing would be much increased. At Macao we print by sufferance, and, of course, with all the disabilities which such a kind of toleration are likely to entail upon us. The expenses of typography would also be greatly diminished; so that, at no great cost, books of instruction might be scattered with an unsparing hand in every direction Artists would also come and settle amongst us, who would furnish drawings and illustrations for our books of science; – now we are obliged to put up with the rude and inaccurate performances of a Chinese, or dispense altogether with helps so important towards an adequate conception of things not seen. There is another advantage that we may mention here, lest it should be forgotten, which is, the Rest of one day in seven, maintained with the decencies and solemnities that belong to the Lord's-day; while the ordinances of religion, and the preaching of the gospel, might be waited upon with that zeal, assiduity and interest, which make them refreshing to our own hearts, and render them lovely in the eyes of mankind. Thirdly. Merchants now resident in China, would find this an easy retreat, whither they might |

retire to prosecute their commercial schemes, whenever the Governor of Canton should think fit to interrupt the progress of trade. It is pretty evident that the sellers of Tea and Silk, if the merchants were stationed only a few days' sail from the coast, with a fair wind both ways, would send the goods after them, if a message with conditions of peace, and a return of the merchants upon their own terms, did not render such a step unnecessary. But I am much mistaken, if, after a settlement had been effected so near China, any attempt to stop or perplex the trade would ever be once thought of; for a son of Han is too discreet a man, especially with all his learned records about him, to try an experiment that must then inevitably terminate in his own confusion. On the contrary, the news of such an event as the colonization of islands at so short a distance from the celestial empire, would produce such a sensation at the court of Peking, and throughout the country, that we should be received in a way very different from that tone of arrogance with which we are now entertained. The doctrines of submission, which, like the venerated relics of antiquity, have been handed down from one generation of merchants to another, have emboldened a Chinese to treat us with insult, and to make sport at our vexation: but when he saw forts, batteries, and men-of-war so near his own threshhold, he would at once think that we had lately |

embraced a new set of tenets, and shape his conduct accordingly. Fourthly. But while we should thus shew ourselves able to maintain our own cause, our Principles and our Practices would have nothing warlike about them. On the contrary, this spot might, under the blessing of the Almighty, be the focus from whence the influences of religion, science, and the sentiments of political freedom, would emanate in an ever-flowing tide. Millions would soon hear, and many thousands see, how men fare when they live under the benign aspect of impartial laws, and religious liberty; compare matters at home with what they were found to be abroad, and thence be led to ask the reason of the difference. Those who labour among the heathen in word and doctrine know the value of such inquiries; and it is pleasing to learn, from observation, that strangers cannot long converse with christians, on amicable terms, without gaining some relish for freedom, or some impression in favour of religion. Thus the great object, in behalf of which so many prayers are now offered up to the Throne of Mercy, would be advanced, namely, the evangelization of this mighty portion of the human family. Fifthly. A Depository would be provided for such stores as are necessary for the repair and refit of ships coming either from the east or the west, and a place where they might lay up the indisposable |

part of their cargo till the arrival of fairer opportunities, and thus be enabled to prosecute the rest of their voyage with as little delay as possible. No arguments will be required to convince shipowners that it is highly desirable to have a port near at hand, where spars, rope, sails, and other necessaries can be had in good order, and at a small advance on the market price in England or America. A ready communication might be established by means of steamers with this place or any other upon the coast, which would carry the superfluities of cargo to the islands, and bring from thence the stores or whatever else might be required, while these superfluities, along with other articles of speculation, might be sent in small vessels to every part of the coast with ease and safety. These small vessels might skim over the seas without danger from the shoals; while the frequency of their appearance would, in time, make them familiar, and at last, obtain for them a license to trade without interruption: and what is not unimportant, the sight of them occurring so often, would indicate that they were not far from home. To effect so desirable an object as the establishment of a colony in the midst of these seas, an appeal must be made to Government, which is never so likely to be successful as when it is backed by the concurrent opinions of an enlightened public. When all acknowledge that something must be done to protect our commerce in these regions from vexation and loss, |

and to gain a better acquaintance with the inhabitants, do not be particular, my countrymen, in the choice of expedients, provided they are just and lawful, but take the first that offers, till you can find a better. The one I recommend is feasible, at least in my judgment and in the judgment of several about me, who have devoted their attention to the subject. Look at your map and turn the matter over in your own mind, and it is not unlikely that you will soon be of the same way of thinking. Some of my christian brethren, in whose prayers I hope the Bible Agency of China has sometimes a share, will say perhaps, that the distribution of God's word and missionary efforts will soon of themselves accomplish all I contemplate, without any extraneous and perhaps, questionable assistance. Upon that head we will not spend a moment's controversy, but these all-powerful instruments for doing good must first have fair play, otherwise they will effect but little or nothing. In order to instruct or convert the people we must get at them, but this we cannot do at present, save by ways and methods so full of degradation, hurry, or annoyance, that our best endeavours are often paralyzed, though we see that the line of our duty runs onward, and the promise of God urges us to follow it with courage and cheerfulness. When I can travel in town or in country with my bag of bibles without the fear, or rather the certainty, of being haled |

before a magistrate, and from thence to a dungeon; and when the missionary can teach publicly and from house to house, without jeopardy of losing his head, I shall then find so much to occupy my mind and engage my heart, that I will consent to leave all worldly projects to be dealt with by wiser heads than my own, and withal, allow my friends in England to inscribe upon their performances, CHINA OPEN, in as large a character as they please, and to descant upon the theme with all the enthusiasm of thought and play of language that a glowing fancy can supply. In the meanwhile you must remember, that between us and a right understanding with China there is a large barrier of ignorance, pride, and prejudice, to remove which every engine, with a firm reliance on God's help, must be used. The occupation of the Bonin Islands would not achieve all, but it would perform a good part in the execution of the work, I have therefore, felt it to be my duty to suggest and recommend it to you. For the arguments here used, and for the mode of handling them, I am myself alone responsible; should they produce conviction in the minds of some, or furnish a hint for reflection in others, and so help to set forward a good design, the credit must be ascribed to T. R. Colledge, Esq., senior Surgeon to his Majesty's Commission, who, by his professional zeal and long: continued exertions for the |

welfare of this people, has earned the title of the Chinaman's Friend, while his patient efforts, to extend and improve our intercourse with the Chinese, commend him to the grateful feelings of his countrymen. His example has been followed by the Rev. P. Parker, M.D. from the American Board of Missions, who has now, for more than twelve months, conducted an Opthalmic Institution at Canton, with great ability and increasing success. To incite some of the medical profession in England to come hither and co-operate in the advancement of the same good work, is the motive for this short en comium, with which I wind up my letter.

G. TRADESCANT LAY.

China, November 27, 1836. |

TRANSCRIPTION NOTESSome tables have been reformatted for clarity in HTML presentation. |

authorname, dates |

BIBLIOGRAPHIC DESCRIPTION

|